Graphic Inquiry:

Graphic Inquiry:

Infusing Visual Techniques and Technologies

We live in a high-tech, multimedia world filled with visual tools and resources, yet many of our classroom activities still emphasize print communication. Even inquiry-based approaches to learning often stress writing lists of questions, reading texts, and writing papers. We know that many of our young people are motivated by graphic communications. There’s a need to explore the potential of graphic inquiry in teaching and learning.

Let's explore three quick examples:

Virtual Adventure. Rather than starting with a topic, begin an inquiry with a virtual field trip. Ask students to explore an exhibit at a science museum and share their experience. Rather than a traditional paper, involved students in creating a poster using a tool like Glogster or Cropmom. One student went on a virtual tour called the Underground Adventure at the Chicago Field Museum. Go to Teacher Tap: Virtual Field Trips and Museums for ideas.

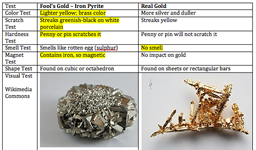

Visual Problem and Solution. Provide students with a visual problem such as a mineral in need of identification. Ask students to organize information visually, indicate actions visually, and show photos.

Visual Reflection. Require a series of process assignments rather than a final product. For instance, after reading Listen to the Wind, students might create a plan for a schoolwide Pennies for Peace project. Then, create a visual showing their thoughts about the process. Use Comic Life for project reflections.

Graphics and the Inquiry Process

Explore learning environments that infuse graphic techniques and technologies throughout the inquiry process to address standards and promote deep thinking.

Inquiry is "a process that involves asking questions and searching for evidence that can be used to design arguments, make decisions, and draw conclusions" (Lamb & Callison, 2010). It's an active process that addresses meaningful questions.

Even before we learn about inquiry in school, each of us begins our life as a inquirer. Read about students as information scientists and Annie's Inquiry and Danny's Inquiry. What did you investigate as a child? What do you investigate as an adult?

Think about how you matured as an information scientist. Read about student maturation and inquiry.

Question

What is the question I’m trying to answer, the problem I’d liked to solve, or the key issue I need to resolve?

What is the question I’m trying to answer, the problem I’d liked to solve, or the key issue I need to resolve?

As yourself, "how do I encourage students to ask deep questions rather than surface level questions?"

Generate a list of questions about Egyptian mummies. Then, look at photographs from Wikimedia Commons and refine the questions. What's the impact of the visuals on your ability to generate questions? How could audio, video, or animation be used in another situation?

A photo of a firefighter might help generate questions such as "Why does he have stripes on his coat", "Why is his helmet yellow.", or "Does he like or hate fires?"

Use historical drawings and painting to stimulate questions about the American Revolution.

Use historical drawings and painting to stimulate questions about the American Revolution.

- Molly Pitcher: Fact or Fiction?

- Was this a real person or a myth?

- When was the event?

- When were the images made?

- Were all the pictures based on an earlier image?

- Is the illustrator bias in some way?

- Is the image realistic or invented?

- How are these images alike and different?

- Which is most accurate?

- Which is most effective?

- Which would I choose to use?

Visual stories are also an effective way to jumpstart an inquiry.

Visual stories are also an effective way to jumpstart an inquiry.

- What are the most important ideas in the story?

- Could the story be told from a different perspective?

- What other types of visuals could be used?

- How would the story be different in another setting?

- Could you tell the entire story without words? How?

- What questions do you have about the story’s topic?

- What are your questions about the people and place?

Brainstorm books that jumpstart questioning related to a particular curriculum-related topic.

Explore news photos, cover stories, and front pages that could be used to generate questions or practice the process of questioning. Go to Newseum and Yahoo Photos for examples.

Contrast dueling images such as an animal in a cage and in the wild.

How could sets of images be used to encourage different perspectives?

In Q Tasks Carol Koechlin and Sandi Zwaan provide questions to get students and teachers thinking about their questions and information to deepen the investigation. Below are som examples.

In Q Tasks Carol Koechlin and Sandi Zwaan provide questions to get students and teachers thinking about their questions and information to deepen the investigation. Below are som examples.

- What other questions might be useful?

- How are the ideas alike or different?

- How will this information help me answer my questions?

- What would this look like from another perspective?

- What are the causes and effects?

- What are the consequences of?

- What if ..?

- What does this imply about…?

- What evidence supports this argument?

- What do you mean by…?

- What do you see?

- What objects go together? Why?

- Which objects should be separated? Why?

- What would you name this group? How would you describe it?

- In what other ways could these objects be grouped?

Explore a set of photographs and use the questions above to deepen an investigation.

Explore

In How To Use Your Eyes, James Elkins urges us to “stop and consider things that are absolutely ordinary, things so clearly meaningless that they never seemed worth a second thought. Once you start seeing them, the world – which can look so dull, so empty of interest - will gather before your eyes and become thick with meaning.” (p. xi)

In How To Use Your Eyes, James Elkins urges us to “stop and consider things that are absolutely ordinary, things so clearly meaningless that they never seemed worth a second thought. Once you start seeing them, the world – which can look so dull, so empty of interest - will gather before your eyes and become thick with meaning.” (p. xi)

Encourage students to explore unusual aspects of a common topic. For instance "I’ve seen many images of WWII in Europe, but I never really thought about the war impacting Australia. I’m going

to refocus my inquiry."

Students often begin by exploring library and online resources. When guiding graphic inquiries remind students about the use of visual resources such as photo collections, atlas, artwork, and illustrated books. Consider the wide range of graphic resources that might provide different perspectives on a subject. For instance, use The Center for Cartoon Studies graphic histories on topics such as Satchel Paige and Houdini.

Provide opportunities for focused exploration. Encourage online nonfiction reading and systematic notetaking with tools such as Weather and Painting.

Exploring leads back to questioning. Questions may be refined, restated, or new queries may emerge. Encourage inquirers to be risk-takers. Ask:

- What can I answer and what new questions do I have?

- How can I focus and narrow my questions?

- Did we miss anything the first time around?

- Are there other ways to think about the same thing?

- Are there other points of view that should be considered?

- Can I think of unusual approaches or different ways of thinking?

Students often forget that inquiry is recursive rather than linear. How will you help students remember to address these questions?

Many students are looking for the quick answer. Encourage students to move from the shallow to the deep end of thinking through supporting cycles of questioning and exploring. In Info Tasks for Successful Learning, Koechlin and Zwann (2001) suggest evaluating the quality of student research questions by asking:

Focus - Does your question help to focus your research?

Interest - Are you excited about your question?

Knowledge - Will your question help you learn?

Processing - Will your question help you understand your topic better?

Assimilate

The process of assimilation involves reinforcing and confirming information that is known, altering thinking based on new information, or rejecting information that doesn’t match the student‘s belief system. In an inquiry, assimilation leads to consideration of new options and points of view. (Callison, 2006, p. 7)

The process of assimilation involves reinforcing and confirming information that is known, altering thinking based on new information, or rejecting information that doesn’t match the student‘s belief system. In an inquiry, assimilation leads to consideration of new options and points of view. (Callison, 2006, p. 7)

As you explore, look for unique aspects of at least 3 pieces of evidence and make comparisons.

Examine images that represent the different phases of mitosis. How are these images alike and different? What are the key elements that reflect each phase?

Help children build arguments. For instance, a child might conclude "I’ve been reading stories from around the world, examining old and new artwork, and learning about what’s real and make believe

about dragons. I found a website that said there are dragons in caves, but I didn’t believe it. The Komodo Dragon is the only real one."

The Trash or Treasure approach is effective in helping young people collect evidence and build arguments.

Many variations of “Trash & Treasure exist.

Share your favorite.

Students need to keep their central question in mind as they work with evidence. For instance, they might ask "what should be done with "road kill"? They will use the visuals collected from sites such as the Wild Images Gallery: The Cycle of Life after Death from Banff National Park in Canada to analyze the question and possible solutions.

Apply the Ds of Evidence to this problem:

- Discover Identify new ideas and ways of thinking about the evidence

Rather than taking the animal to a landfill, we could leave the animal where it dies.

- Discern Identify the origins of information and underlying thinking

We need to think about the needs of the scavengers.

- Detect Seek out fallacies, flaws, and misinformation along with reasons for these errors.

In some cases, they drag the animals into the woods. This is different than just leaving them where they die.

- Deduce Identify possible conditions and consequences

There are scavengers in both rural and urban areas.

- Divide Organize information by comparing how people, places, and events are alike and different. Also, classifying information into categories based on commonality

Different animals would be killed depending on the area and different scavengers would eat them.

- Dictate Identify themes, patterns, and generalizations

There's a cycle of life after death that repeats itself everywhere.

- Devise Build arguments by organizing evidence

Animals will disappear on their own in a couple weeks.

The Ds of Evidence can be applied to any topic such as The Lost Colony of Roanoke.

The Ds of Evidence can be applied to any topic such as The Lost Colony of Roanoke.

My teacher asked me to select an image that represents the main idea of my inquiry. I'm applying the Ds of Evidence to see if this illustration by John White really emcompasses my understanding of the native people at Roanoke during the 1500s.

John White (1540-1593) was an artist and become govenor of Roanoke Colony. His were some of the earliest images by Europeans depicting native people. The recreations at historical sites match White's images and the materials available for construction in the 1500s. In 1590, Theodor de Bry copied White's work, but distorted the images.

Select an image that represents the main idea of an investigation. Apply the Ds of Evidence to this image.

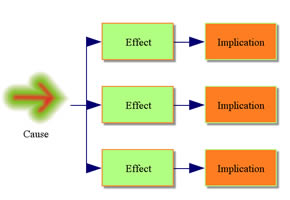

Although assimilation occurs deep within our brain, we can use visual activities to build these associations. Marzano, Pickering and Pollock (1997) identified six graphic organizers that correspond to six common information organization patterns:

- Descriptive patterns. Webs are used to represent facts about people, places, things, and events.

- Time-sequence patterns. Timelines and cycle diagrams organize events by chronology.

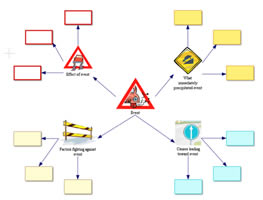

- Process/cause-effect patterns. Fishbone charts and “how do” diagrams organize information into a causal network or into steps leading to products.

- Episode patterns. These visuals organize information about specific events including setting, specific people, duration, sequence, and cause and effect.

- Generalization/principle patterns. Use hierarchies to organize information into general statements and supporting evidence or examples.

- Concept patterns. Use concept maps to organize classes and categories about people, places, things, and events.

These patterns can be applied to syrup production.

Infer

Evidence is necessary to support a claim, justify change, or make an informed decision. Students must learn to identify, process, and judge evidence. This begins with looking for patterns of evidence. Ask:

Evidence is necessary to support a claim, justify change, or make an informed decision. Students must learn to identify, process, and judge evidence. This begins with looking for patterns of evidence. Ask:

- What evidence is most useful in addressing my questions?

- How does this evidence connect with what I already know?

- How is this evidence relevant for my question?

- What are my assumptions?

- What am I guessing about and what do I know for sure?

- What evidence is from primary versus secondary sources?

- Which sources are bias and which are credible?

- What are all the possible perspectives and viewpoints?

- Why would someone consider one viewpoint better/worse?

- What pieces of evidence support and refute a perspective?

- What are the most important pieces of evidence?

- What are the supporting pieces of evidence?

- What are the patterns of evidence?

- What new questions does this evidence raise?

Rethink an assignment.

Focus on the collecting evidence and building convincing arguments.

Arguments provide evidence to support a claim. To develop useful arguments, inquirers must evaluate evidence, examine different points of view, and determine the most logical approach or meaningful conclusion. Ask:

- How does the evidence fit together?

- What claims and supporting arguments could be made?

- How can the evidence be arranged to support a conclusion?

- What’s the core of the argument?

- What pieces of evidence support what perspectives?

- How do the arguments fit with my understandings?

- What is the reasoning behind each argument?

- What are the limitations of these arguments?

- What are the errors in reasoning?

- Where are the holes in the evidence?

- How could this information be misleading?

- What are the problems and barriers?

- How could it be corrected or improved?

- What are the relationships/causes/effect?

Discuss the different perspectives on how wildfires should be managed.

Use the questions above as a guide.

Deductive arguments apply general principles and theories to specific situations. This

is the most effective educational technique. Students are asked to explain their

hypotheses, experiments and conclusions.

Provide opportunities for students to try out their ideas and apply what they've learned to real-world problems. For example, children might apply the four principles of flight to predict which paper airplane will work best. Rather than simply reading about machines and write a report, children design and test an invention. Go to the Forces of Flight website.

Another approach is to ask students to turn facts into a visually convincing argument that can be shared. For example, show me why you think the penny should or shouldn't be discontinued. Or, show me that this computer game is or isn't an accurate reflection of history.

When designing persuasive messages, ask:

- Who is my audience and what do they need to know?

- What are examples and nonexamples?

- In what ways can the evidence be presented to communicate the argument?

- How can my messages be shared in an effective, efficient, and appealing way?

- How can my message be conveyed in a number of different ways?

- What parts of the argument are difficult to understanding?

For instance, children may become "machine detectives." After collecting information at EdHeads about simple machines, their job is to collect evidence of simple machines by identifying and photographing them in the library.

In most academic situations, inquiry involves accumulating evidence that supports inferences that seem reasonable, logical, and persuasive. Students ask:

- What inferences can I make based on the evidence?

- What conclusions can I draw?

- What decisions can I make?

With each inquiry cycle, inquirers must revisit questions with an open mind.

- What evidence do I still need to gather?

- What has changed since my last cycle of questioning, exploring, assimilating,

and inferring?

- Have I visualized the evidence in many different ways?

- What pieces of information still need to be connected? What’s not obvious?

- Are there alternatives I haven’t considered? Are there opinions I should seek?

- What are the risks and benefits of each approach?

- What generalizations can I draw based on the evidence?

- Do I have enough information to draw a conclusion or make a decision?

- How do I most effectively present arguments and cite evidence?

- How can graphics be used to better understand the data and my conclusions?

Reflect

After rounds of questioning and exploring, assimilating and inferring, ask students to revisit the questions and goals of their inquiry. How did the project evolve?

After rounds of questioning and exploring, assimilating and inferring, ask students to revisit the questions and goals of their inquiry. How did the project evolve?

Encourage products that build in metacognitive aspects and opportunities for reflection. Examples:

Rather than just copying from Wikipedia, I thought about what a tourist would really want to know about the desert.

I’ve created both a family timeline and a Civil Right Movement timeline so we can talk about how each member of the family might have been impacted by what was happening nationally.

My exploration of music from the 1850s lead me to songs about fashion. I create a song in GarageBand that’s a parody of the fashion industry.

Inquiries may go in different directions depending on the questions. While some inquiries look for answers, others seek solutions. The goal may not be apparent in the first round of the cycle. By encouraging inquirers to reflect throughout the process, inquiry becomes a cycle building deep understandings. Ask:

Inquiries may go in different directions depending on the questions. While some inquiries look for answers, others seek solutions. The goal may not be apparent in the first round of the cycle. By encouraging inquirers to reflect throughout the process, inquiry becomes a cycle building deep understandings. Ask:

- Did my question(s) reflect my need or problem?

- Have I been successful in answering my question(s)?

- Were my search strategies flawed?

- Could my information be biased or incorrect?

- Is this the best information to address this question?

- Could I have made incorrect connections?

- Could the inferences identified be flawed?

- Have I addressed the needs of my audience?

- What new questions have arisen from the evidence?

- Have I chosen the best conclusion or decision?

- Am I satisfied with my progress?

- What are my strengths

Graphics Inquiry and the Dust Bowl

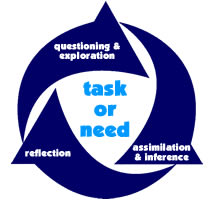

Annette Lamb (1997) developed a model called the 8Ws using everyday terms to describe the inquiry process. The Ws are explained below within the context of Callison's components of information inquiry. Daniel Callison (2002) identified five components of information inquiry: questioning and exploration, assimilation and inference, and reflection. Callison states that inquiry can address a workplace or professional problem, academic information task assigned by a teacher, or personal information need. When these three areas overlap, authentic learning can occur.

Questioning and Exploring

Questioning and Exploring

The inquiry process begins with an open mind that observes the world and ponders the possibilities.

Watching asks inquirers to become observers of their environment becoming in tune with the world around them from family needs to global concerns. Encourage young people to read the new at USA Today, CNN, CBC, BBC, Reuters, and other news outlets.

I've been watching video, looking at photos, and examining maps about climate change in online news such as USA Today and it made me think about our past and the future. Could the Dust Bowl of the 1930s happen again? What caused it? What environmental changes will happen with climate change?

Wondering focuses on brainstorming options, discussing ideas, identifying problems, and developing questions.

According to the Sanora Babb website, "Random House accepted 'Whose Names Are Unknown' for publication in 1939, then rescinded the contract when Steinbeck's 'Grapes of Wrath' appeared the same year to great acclaim." The books each represent the same time period in different ways. I wonder which is most accurate? Visit the Sanora Babb website to learn more and see photographs.

Exploration involves observing the world, investigating possibilities, collecting resources, interviewing experts, and experimenting with ideas.

Webbing involves students in identifying and connecting ideas and information. Data is located and relevant resources are organized into meaningful clusters. One piece of information may lead to new questions and areas of interest.

I've been thinking about the Great Depression and specifically the Dust Bowl. I starting exploring books such as "Years of Dust" and "Children or the Great Depression" and online photographs at the Library of Congress such as the Voices from the Dust Bowl collection and curriculum materials from the National Archives. Migrant Mother is a powerful photograph. I've been collecting information about Dorothea Lange's photographs during the 1930s. Are her famous images intended to document the Great Depression or provide propaganda for the government? I hoped that reading the book "Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits" would provide some answers about the photographer and her intentions. It makes sense to tell her story through photos. Here's a photo of Dorothea Lange taken in 1936 around the time she took the famous photograph of the migrant mother. I explored many photographs at Wikimedia Commons which took me back to the original sources.

Exploring leads back to questioning. Questions may be refined, restated, or new queries may emerge.

Assimilating and Inferring

Assimilation involves processing, associating, and integrating new ideas with already available knowledge in the human mind. This can be the toughest phase for young people because they may be uncertain about what they've found and where they're going.

Wiggling involves evaluating content, along with twisting and turning information looking for clues, ideas, and perspectives.

Inspiration templates are useful in organizing information. Inspiration provides two templates that focus on causality and cause/effect that would be useful for this type of thinking.

What caused the Dust Bowl? What was the relationship between the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression? What was the impact of each event? How did they impact each other? Could these two events happen again either together or separately?

Next, young people apply evidence to solve problems and make decisions.

Weaving consists of organizing ideas, creating models, and formulating plans. It focuses on the application, analysis, and synthesis of information.

The National Archives provides new online tools called Docs TEACH. This tools provides a framework for exciting activities.

I created a map activity at the National Archives that show how and why people moved West during the Great Depression.

I created a scrapbook diary for different elements of the Great Depression such as the economic and social aspects. This scrapbook helps me organize my thoughts and also put myself in the shoes of a person living at that time.

As students weigh evidence, they may go back and collect additional information to support their inferences. This process of assimilation and inference reoccurs as young people accumulate information.

As students weigh evidence, they may go back and collect additional information to support their inferences. This process of assimilation and inference reoccurs as young people accumulate information.

Reflection

As students make decisions and solve problems, they think about the process and consider how to share their conclusions and plan for future inquiries.

Wrapping involves creating and packaging ideas and solutions. Why is this important? Who needs to know about it? How can I effectively convey my ideas?

I'm interested in the impact of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl on children. I created a story by remixing historical video and images. After reading the book "This Land Was Made for You and Me", I decide to incorporate music by Woody Guthrie. If I share it on YouTube, lots of people will see it.

Waving consists of communicating ideas to others through presenting, publishing, and sharing. How will I market my ideas and who will I ask for feedback?

Waving consists of communicating ideas to others through presenting, publishing, and sharing. How will I market my ideas and who will I ask for feedback?

As read nonfiction books and looked at the many photos, I wondered about the lives of the people represented in the images. I decided to Integrate historical photos into a fictional graphic story that infuses factual information. I'm using Comic Life. I'm going to talk my friends into adding their short stories to mine. If we get enough, we could publish then using CreateSpace.

Wishing involves assessing, evaluating, and reflecting on the process and product of inquiry. Was the project a success? What will I do next?

After learning about the Dust Bowl, I thought it would be fun to learn more about the tall tales of the time period. I began another round of inquiry. I read the graphic novel The Storm in the Barn by Matt Phelan. Then I read a Jack Tale (Source 1, Source 2). I compared photos of the time period with historical drawings/ Then, I wrote a tale tale using Scratch software and images from Open Clipart Library.

Print Resources

- Children of the Great Depression by Russell Freedman (Juvenile Nonfiction)

- Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits by Linda Gordon (Biography)

- Dust for Dinner by Ann Turner (Beginning Reader)

- The Dust Bowl Through the Lens by Martin W. Sandler (Juvenile Nonfiction: Photography)

- Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck (Teen/Adult Fiction)

- Years of Dust: The Story of the Dust Bowl by Albert Marrin (Juvenile Nonfiction: Photography)

- The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dust Bowl by Timothy Egan (Adult Nonfiction)

- Out of the Dust by Karen Hesse (Teen Fiction)

- The Storm in the Barn by Matt Phelan (Juvenile Graphic Novel)

- This Land was Made for You and Me by Elizabeth Partridge (Juvenile Nonfiction)

- Whose Names Are Unknown by Sandora Babb (Novel)

- Wingwalker by Rosemary Wells and Brian Selznick (Juvenile Fiction: Easy Chapter Book)

Video Resources

- American Experience: Surviving the Dust Bowl

- The Plow that Broke the Plains from Google Video (NARA)

Images Resources

- Flickr: Dorothea Lange, Dust Bowl - The Depression Years, Picturing the 1930s, FSA/OWI Favorites

- Library of Congress: Photographers of the FSA, Voices from the Dust Bowl, Documenting America, Popular Requests, Staff Selections

- Shorpy Image Galleries

For a more in-depth exploration, read the graphic book Graphic Inquiry by Annette Lamb and Danny Callison available from Libraries Unlimited, 2011.